You’ve probably seen the phrase “universal masking” online or in the news by now. Government officials and health experts have been discussing the idea of wearing a protective mask out in public, regardless of whether you are showing symptoms of COVID-19 or not, in an effort to curb the spread.

There’s so much information right now, and not all masks are created equally. It’s perfectly natural to feel a bit overwhelmed by all of the information, or feel unsure about which mask types or fabrics work best (or at all) for certain applications, but this is critical knowledge if you’re brokering sales on masks for medical facilities or other applications.

The consensus among medical experts is that some sort of mask is at least better than nothing.

“If you are likely to be in close contact with someone infected, a mask cuts the chance of the disease being passed on,” The Guardian wrote.

The CDC has found evidence that people infected with the coronavirus, but are asymptomatic, are still capable of transmitting the virus, making masks a vital precaution for everyone.

NPR reports:

The primary benefit of covering your nose and mouth is that you protect others. While there is still much to be learned about the novel coronavirus, it appears that many people who are infected are shedding the virus – through coughs, sneezes and other respiratory droplets—for 48 hours before they start feeling sick. And others who have the virus—up to 25 percent, according to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Director Dr. Robert Redfield—may never feel symptoms but may still play a role in transmitting it.

So, regular folks (i.e. not health care professionals) who are going out in the world in a very limited capacity (i.e. essentials only) would be wise to wear a face covering of some sort, but there are obviously a lot of variables to consider here.

Types and Recommended Uses

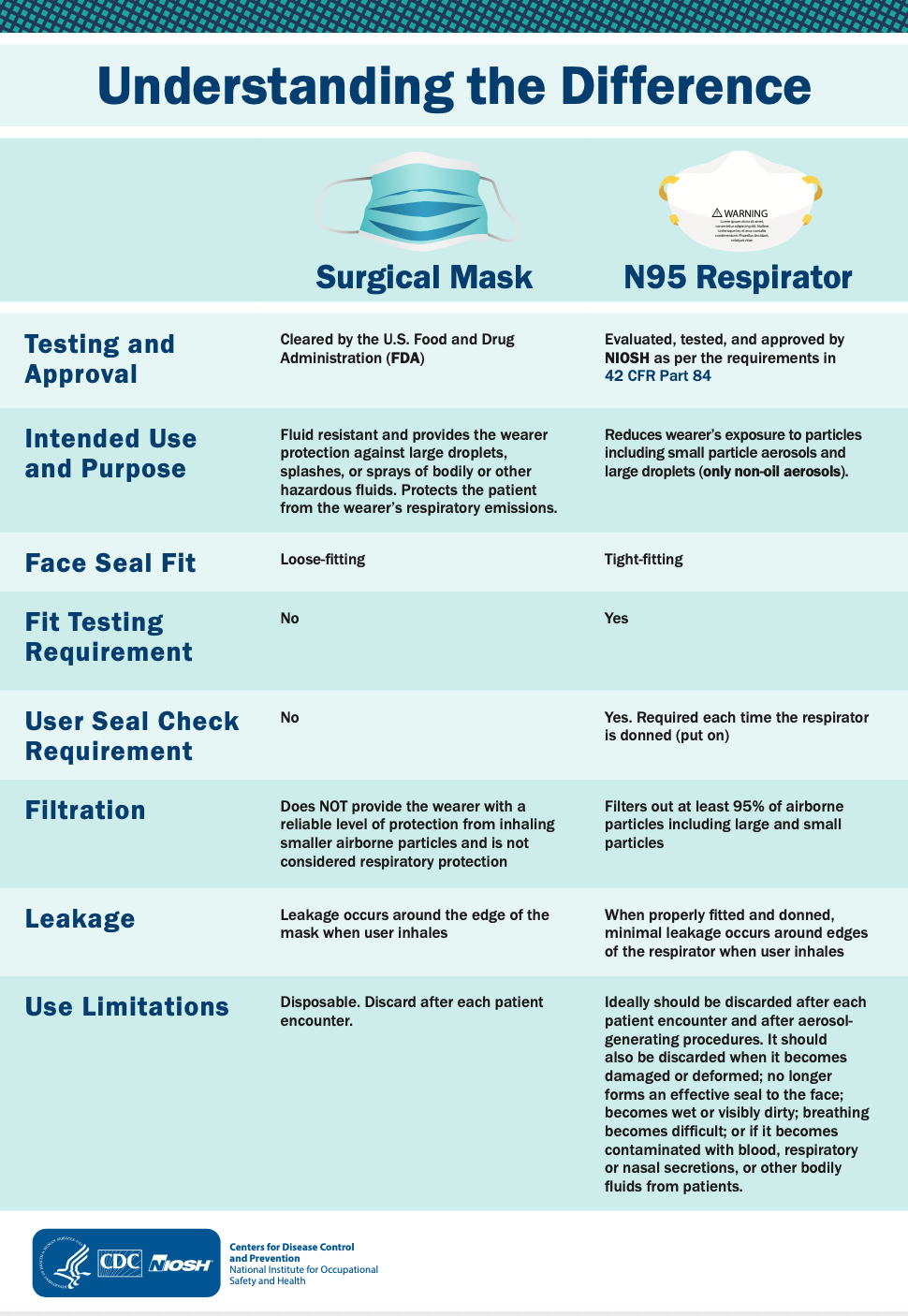

First, let’s look at the different mask types. The CDC published a handy infographic depicting the differences between surgical masks and N95 respirators:

There are also several standards of medical-grade masks similar in performance to the K95. These include the KN95 (China) and FFP2 (Europe). While not all of them have been approved for medical use in the U.S., many of them have, with the FDA most recently approving the K95 for use. Here is a breakdown of these mask types from 3M.

All N95 masks are not the same, however. Some are made with valves, which have actually been outlawed in California’s Bay Area, according to Fast Company. Basically, everyone should wear a mask in public, but not if it has a valve.

The problem with the valve, experts say, is that while it filters out pathogens for the user, it doesn’t protect others from any pathogens coming from the person wearing it. When you breathe out while wearing one, the valve opens, creating an open pathway for the virus and other particles to escape.

The N95 masks are typically reserved for health care professionals anyway, but should others decide to use them, the difference between one with a valve and without a valve is an important distinction to make. Many N95 respirators you might find in a hardware store will have the vent, because these were designed with home improvement projects in mind, not protecting others from the spread of disease.

Surgical masks, the looser-fitting fabric mask that you’ve likely seen people wearing at the grocery store, are fluid resistant and protect people from “large droplets, splashes or sprays of bodily or other hazardous fluids.” They also keep the wearer from spreading their own respiratory emissions. For COVID-19, which experts say is most easily spread by large droplets spread from a carrier from within about a 6-foot distance, this is a solid protector for lifestyle use.

I does, however, allow for leakage around he edges of the masks when the user inhales, because of its looser fitting nature, which makes the N95 respirator more effective for health care professionals or people who come into contact with the sick. The N95 masks also filter out at least 95 percent of airborne particles, whereas the surgical mask does not. A surgical mask’s filtration efficiency is roughly 60 to 80 percent.

However, N95 and similar masks should be, for the most part, limited to health care professionals.

Mask shortages have been a very real thing, and taking the supply away from medical professionals is dangerous. Apparel companies like Los Angeles Apparel, Hanes, Fanatics and more are using their capabilities to create face masks for both health care workers and everyone else, and plenty of people have been making their own at home.

Materials

With N95 and surgical masks left for medical professionals and the CDC advising widespread mask usage for the general population, a new market has emerged for fabric masks designed for everyday wear. This brings into question the best type of face mask material.

The CDC posted a no-sew mask pattern using a bandana and coffee filter, and posted videos on using rubber bands and folded materials commonly found at home.

These kinds of masks limit the spread of the wearer’s own germs, in the chance they are infected but asymptomatic. But for protecting against incoming germs, material and fit is important.

The New York Times reports:

In recent tests, HEPA furnace filters scored well, as did vacuum cleaner bags, layers of 600-count pillowcases and fabric similar to flannel pajamas. Stacked coffee filters had medium scores. Scarves and bandanna material had the lowest scores, but still captured a small percentage of particles.

Homemade masks made of high quality, high thread count cotton have proven to be almost as effective as professionally manufactured surgical masks, with a range of 70 to 79 percent filtration.

There’s also a trick to see how effective fabric masks are.

“Hold it up to a bright light,” Dr. Scott Segal, chairman of anesthesiology at Wake Forest Baptist Health who recently studied homemade masks, told the New York Times. “If light passes really easily through the fibers and you can almost see the fibers, it’s not a good fabric. If it’s a denser weave of thicker material and light doesn’t pass through it as much, that’s the material you want to use.”

Again, it’s important to note that the common person going to the pharmacy for the ever-elusive roll of toilet paper or to restock on groceries likely does not need the medical grade protection of an N95 mask if they are not coming into direct contact with someone infected with COVID-19, but precautions are still necessary.

The challenge for a lot of people and companies making masks is finding something that has high filtration ability but is still breathable.

“You need something that is efficient for removing particles, but you also need to breathe,” Dr. Yang Wang, an assistant professor of environmental engineering at Missouri University of Science and Technology and award-winning aerosol researcher, told the Times.

In the context of reserving N95 masks for frontline health care professionals, Dr. Wang’s research looked at allergy-reducing HVAC filters, which captured 89 percent of particles with one layer and 94 percent with two layers. Furnace filters captured 75 percent with two layers, and 95 percent with six layers.

Cotton—especially tight-weave varieties—has been, for the most part, very effective, which makes it even more heartening to see apparel companies spring into action.

Dr. Wang’s study also found that the best homemade mask designs were made with two layers of high-quality, heavyweight “quilter’s cotton,” a double-layered mask with batik fabric, and a double-layered mask with an inner flannel layer and outer cotton layer.

While some infectious disease experts advise against synthetic or polyester fibers for masks, as studies show the virus survives longer on these fabrics, non-medical masks should be washed after each use anyway, reducing the risk.

The New York Times report says consumers looking for similar results in a mask should look for a minimum efficiency reporting value (MERV) rating of 12 or higher or a micro particle performance rating of 1900 or higher.

Before anyone rushes out to get masks with certain filters, it’s important to note that they could shed small fibers that would he hazardous if inhaled.

The New York Times again:

So if you want to use a filter, you need to sandwich the filter between two layers of cotton fabric. Dr. Wang said one of his grad students made his own mask by following the instructions in the CDC video, but adding several layers of filter material inside a bandana.

Layering is really a key component of effectiveness here. Even a thick wool scarf, which filtered 21 percent of particles in two layers, more than doubled its effectiveness when layered four times.

What the Experts Are Saying

Regardless of what face covering wearers use, rest assured it is better than nothing, even if it’s just a bandana.

“So it’s not going to protect you, but it is going to protect your neighbor,” Dr. Griffin said. “If your neighbor is wearing a mask and the same thing happens, they’re going to protect you. So masks worn properly have the potential to benefit people.”

And finally, it’s not just the act of wearing a mask to consider. There are other precautions just as vital and lifesaving. First and foremost, don’t touch the front of the mask.

“That’s what I see all the time,” Dr. Griffin added. “That’s why in the studies, masks fail—people don’t use them [correctly]. They touch the front of it. They adjust it. They push it down somehow to get their nose stuck out.”

Once users are done wearing your mask for the day, they should immediately wash it. If it’s disposable, throw it away.

“[Masks are a] reminder that we need to be taking these precautions and serve as a reminder to people to keep that 6-foot buffer,” Joseph Allen, an assistant professor of exposure and assessment science at Harvard University’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health, told NPR. “It should be seen as a badge of honor. If I’m wearing a mask out in public, it means I’m concerned about you, I’m concerned about my neighbors, I’m concerned about strangers on the chance that I’m infectious. I want to do my part in limiting how I might impact you.”