Campaign merchandise. It’s something we’ve discussed ad nauseum at this point due to our niche subject matter, but it’s actually important! It provides a visual representation of a political candidate’s personal brand and views, and allows others to showcase their beliefs and infer what others’ beliefs are, too.

To put it simply, when you see someone with a candidate’s merchandise or a bumper sticker on a car, you can use that to pretty much judge their entire being. You know what they stand for and against for the most part, and you know by and large what issues they hold dear.

So, is there even really a point to politicians having their prospective policies or stances on important issues on their campaign site? If so, which is more important, the policy or the merchandise?

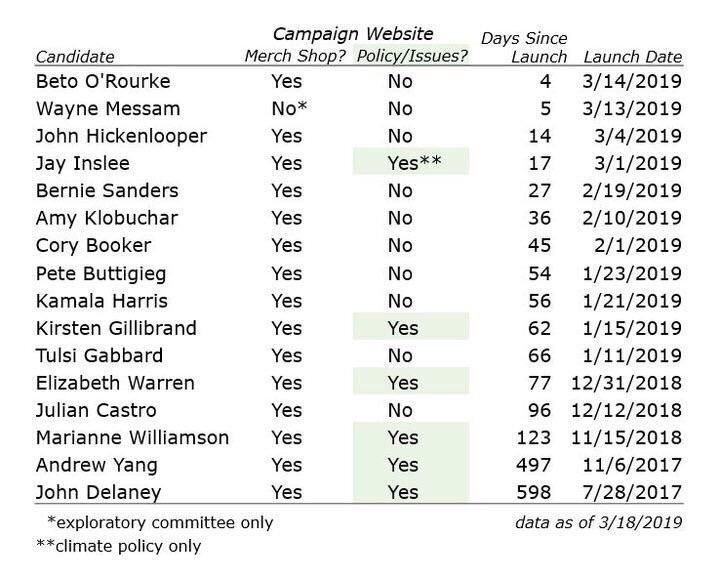

Here’s a really interesting layout of what the current Democratic field of presidential candidates for 2020 looks like, courtesy of Reddit user u/me-myself-and-irene on the Beto 2020 subreddit.

As you can see, 15 out of the 16 Democratic candidates have campaign merchandise on their store. Compare that to the six out of 15 who have actual information about their planned policies. One of them (Washington Gov. Jay Inslee) only has his stance on climate policy.

This isn’t a knock on the candidates. It’s only just 2019 right now, so it’s not crucial for them to have their entire presidential campaign mapped out in full. But, by that same logic, is the merchandise important, too?

Why focus on the merchandise first, rather than the policy?

The answer is that it builds a brand right away. The policies will be explained likely in appearances and speeches, but at those speeches (which will likely be televised or, at the very least, photographed), people will be wearing or holding campaign merchandise in the frame. And, more than that, it’s a seriously effective fundraising tool for candidates courting small-dollar donations.

Also, you can cut a little slack to newer candidates like Inslee, Beto O’Rourke, Wayne Messam, John Hickenlooper and Bernie Sanders, whose campaign sites are younger than a month old.

On the surface, it looks like the majority of candidates are taking a “build the brand first, flesh it out later” approach. If they can garner hype and attention to their campaign (i.e. an audience) they then can fine-tune the whole thing by actually explaining what they plan to do.

It makes sense. And it also underlines the power promotional products have in the campaign cycle (and in general). For many of these candidates, this was the first step. That says a lot.

More than a web page about policy does, it seems.